Some of Our Substations are Missing

Why do British electricity substations keep catching fire?

I recently wrote an article for the Telegraph about a series of unexplained electrical substation fires across the country. There had been eight in the space of a few weeks between March and mid May, when normally you might expect one or two every few years.

The James Bond baddie Auric Goldfinger (played in the film by the great Gert Frobe) had a simple rule of thumb when it came to how many times seemingly innocent mishaps could recur before he perceived a more sinister pattern. “Once is happenstance; twice coincidence; three times is enemy action,” he said.

So was it enemy action in this case, or perhaps something even more sinister; that the people charged with running the network weren’t keeping it in sufficiently good repair?

If you’re interested, you can read the whole article here. It describes eight fires starting in Lancing, West Sussex, in early March and concluding on 12 May with a second fire in the space of a few weeks at the Aberdeen Place substation in Maida Vale, West London.

The most significant of these erupted on 20 March, when a transformer exploded at the large North Hyde substation near Heathrow Airport, severing power to 71,655 domestic and commercial customers in the West London area and also knocking out flight operations at Heathrow.

Europe’s biggest aviation hub closed for more than a day, disrupting over 1,300 flights and almost 300,000 passengers, as well as costing the airlines an estimated £50-100 million in lost revenue. “It was an eloquent demonstration of how a single point of failure could bring chaos to a crucial piece of the British economy,” I wrote.

But was it enemy action? Well, it was hard to find any hard evidence of foreign sabotage being responsible for the damage, despite some unconnected but hard evidence of Russia having been involved in at least one arson attack on a Ukrainian owned warehouse in East London.

Certainly none emerged in any of the eight cases, even though a question mark hangs over a fire at a substation in Glasgow close to the BAE warship yard in Govan (whose electricity was actually knocked out by the fire). Two unnamed individuals have been arrested in connection with a “wilful fire”, but the Scottish Crown Office does not appear yet to have decided whether to prosecute. Watch this space.

Therefore I had some sympathy for the opinion offered by a former member of British military intelligence, Col Philip Ingram, who concluded that, while not completely beyond the bounds of possibility, sabotage seemed less likely.

“Experts I have spoken to with access to very sensitive areas say they have no evidence of anything untoward going down,” he said. Instead, he’d come to believe the fires were more a case of cock-up than foreign conspiracy. “My primary view is that old infrastructure and poor maintenance - or the lack of maintenance - may be responsible for a lot of what we are seeing,” he observed.

This week we received a bit more information to support the colonel’s revised suspicions. On 30 June, the UK grid overseer, NESO. issued its final report on the events of 20 March. You can read the report here.

As I’d pointed out in my article, perhaps the most striking fact buried in NESO’s interim findings (published in early May) was the sheer age of the equipment involved: “The 275 kilovolt (kV) transformer blamed for the blaze was one of two installed when the substation was itself built in 1968, and manufactured by Hackbridge & Hewittic, a British brand name that disappeared in the early 1970s.”

The final report gave as the “most likely cause” for the failure of this venerable item that “moisture [had entered] the bushing causing a short circuit. The electricity likely then ‘arced’ (causing sparks) which combined with air and heat to ignite the oil, resulting in a fire.” So-called bushings are the connections through which high voltage power enters the transformer to be stepped down to a lower voltage. The oil is designed to be an isolator.

NESO also pointed out this failure had not been unanticipated. In 2018, seven years before the fire, “an elevated moisture reading in one of SGT3’s bushings had been detected in oil samples taken in July 2018”, it said. This is more significant than it first sounds. Moisture ingress is a particular concern with transformers, a former CEGB engineer told me, as it can reduce the insulation properties and increase the risk of electricity arcing and fires. Such contamination inevitably becomes more likely with age.

Indeed, according to the guidance issued by National Grid Electricity Transmission - the owner of the North Hyde transformer - such readings indicate ‘an imminent fault and that the bushing should be replaced’. But despite this rule, and the age of the equipment in question, not only was the bushing not replaced but the transformer received no basic maintenance overhaul between 2018 and the date of the fire.

NESO also noted that the fire had spread because the substation did not have proper firewalls between the three transformers on site, which allowed the fire to spread from one to the next and ultimately took all three off line. Although such firewalls have been mandatory in new substations since the 1970s, there is no requirement to retrofit. The fire suppression system at North Hyde was also known to be faulty.

Two points emerge from all this that are concerning to my mind. First is that owners like National Grid seem so laid back about maintenance. In this case, despite a host of red flags about the state of the equipment, the last basic maintenance on the North Hyde transformer had been done in 2018, and the last major overhaul in 2012 - more than a decade before.

Second is the tendency for such companies to rely on ever older equipment. Britain now has an extremely aged network, with around 40% of the assets on it dating from before 1975 - the last time the country invested heavily in the grid as it completed its electrification.

Of course, just because gear is old doesn’t mean it’s not capable of working adequately. And engineers say the old transformers on the system are fantastically robust and were always capable of lasting far more than the 40 years their manufacturers designed them for. But there’s a suggestion that the companies have a less than innocent incentive for deferring their replacement.

It all goes back to privatisation in 1989, when the new private transmission and distribution companies popped out of the Central Electricity Generating Board, its Scottish cousins, and the 12 local area boards. In the new world, regulators not only set prices; they determined how much companies could spend on (and charge the customer for) replacing worn out electrical gear. Margaret Thatcher’s government wanted the system to reward efficiency, so if the companies could do it for less than the watchdog’s capex “allowance”, they got to keep the difference.

Initially, most of these companies were listed on the stock market, but over the years, like much of British infrastructure, they were snapped up by specialist investors. For instance, UK Power Networks is owned by funds connected to Li Ka-shing, the Chinese billionaire, while Northern Powergrid belongs to Berkshire Hathaway, the investment vehicle of Warren Buffett.

“As one might expect, these financially-driven owners responded to the regulatory incentives. Over the past decade, they have generally underspent their allowances for replacing equipment, banking the extra income and helping to make electricity transmission and distribution one of the highest margin sectors in the country,” I wrote. Between 2014 and 2021, transmission companies undershot their replacement capex allowance by 28%, according to Ofgem data, while for distribution companies between 2016 and 2023, the figure was 12%.

Recent analysis by CommonWealth, a left of centre think tank, estimates they collectively spent just £3.1 billion annually last year on replacing equipment against an approved budget of £3.6 billion.

The risk with this approach - which splits the “gains” between the companies and their customers - is that it perversely encourages the companies to skimp on replacing assets - even when that capex might be needed. By setting broad rules which require companies to deliver outcomes such as network performance targets while letting them decide how (and if) to spend the allowance, Ofgem may think it is empowering companies to be more efficient. But insiders point to a culture of “asset-sweating” that has left most substations with primitive analogue control systems, ancient concrete gantries, and a lack of modern monitoring gear designed to forestall outages.

“This old gear can’t last forever,” warns Mathew Lawrence of CommonWealth, adding that when companies are challenged about skimping on capex, they say: “‘Ah, but we will catch up when it’s really needed’. It’s like a football manager who loses his first five games saying he’ll win the next seven.”

Many electricity insiders dismiss the idea that elderly gear poses any risk to the network; or indeed that it has degraded the service in any way. According Simon Gallagher of UK Network Services, a consultant: “The networks are performing better than they ever have.”

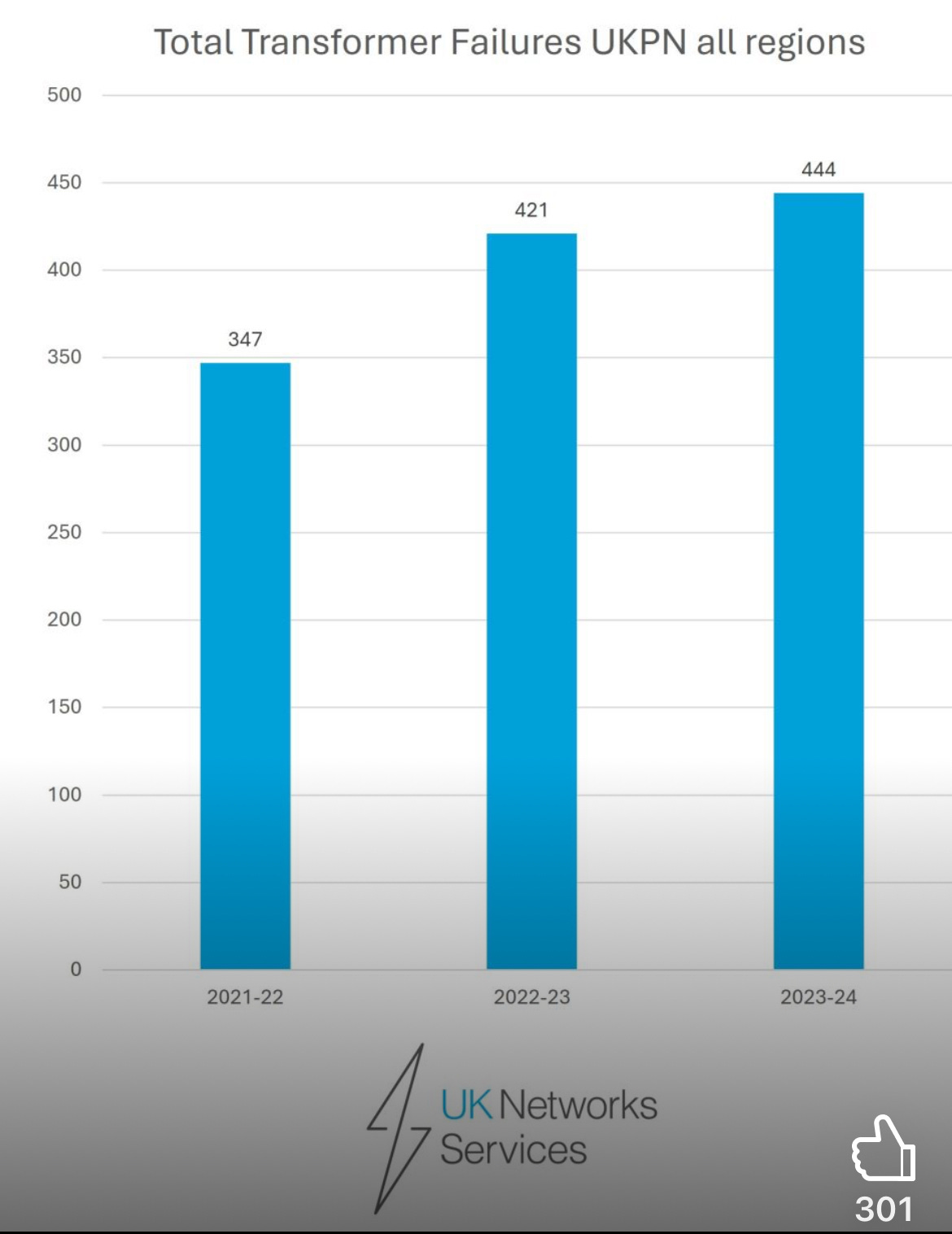

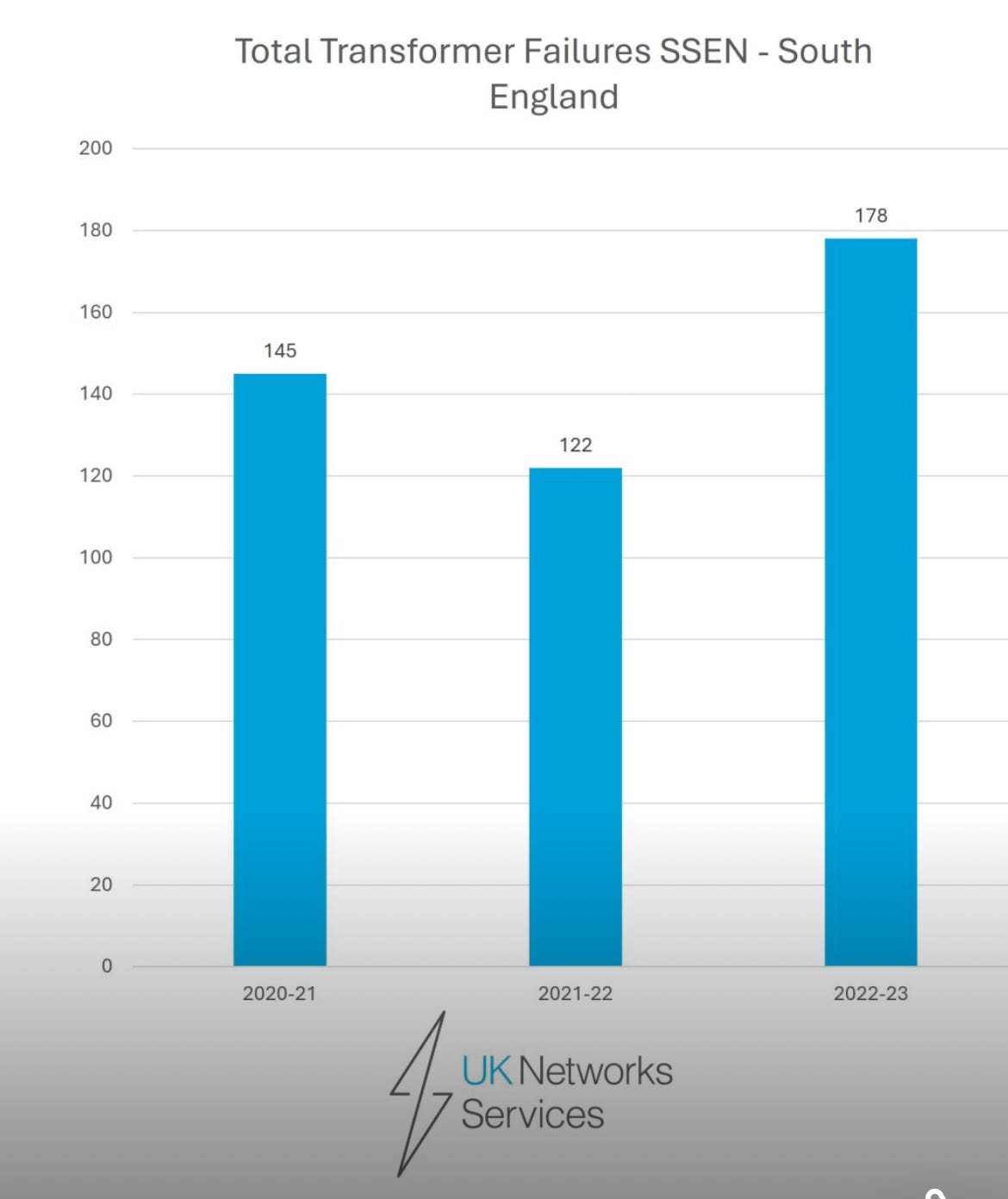

He provided me with some data about the number of transformer failures for two distribution companies, UK Power Networks (Li Ka-shing’s company) and the central and southern England part of SSE Networks (SSEN) over the past three years. The UK Power Networks graph is above and here below are the SSEN figures.

Gallagher’s interpretation was that “transformer fires , while rare and highly visible, have always occurred. There is no evidence of a recent spike in fires or failure rates”. My view was that it was very hard to know what the data is actually saying - not least because it only covers three years and just three of the 12 regional Distribution Network Operators or DNOs.

But it is worth pointing out that in the case of both groups it did show an increase - of 28% over 3 years for UK Power Networks and 23% for SSEN (S. England).

My point however is not that the system is necessarily collapsing now: we just can’t know. And as Gallagher says, “the lights stay on 99% of the time”, while in NESO’s latest annual transmission review, so-called loss of supply incidents actually fell in number over the past five years, although the aggregate amount of electricity lost was greater.

The real worry is the backlog of capex that is inevitably building up. Some time that stuff will have to be replaced: but when? “Old bicycles tend to break more often,” was the comment one former National Grid engineer made to me. What happens when a bunch of elderly transformers does finally start to give up the ghost in a sudden rush?

It’s not an unimaginable outcome. After all, the strain on the UK’s electricity system is rising. Until now, the network’s assets have aged against a backdrop of declining usage, easing the pressure on hard-pressed substations. Britons consumed just 318 terawatt hours of electricity last year; 23% less than the peak year of 2005.

Now, as Keir Starmer’s government presses on towards Net Zero, usage should start shooting up as more sectors (like motor transport and domestic heating) flip from fossil fuels to electricity. Other power hungry applications such as AI are also coming over the horizon. By 2030, NESO anticipates demand will have grown by almost a third to 411 terawatt hours.

The increment to supply that will be needed will come from renewables, such as wind and solar. These create other concerns, such as “dirty power” - a phenomenon linked to intermittent renewable generation sources where, instead of operating at a stable 50 hertz, the power supply’s frequency jumps around and becomes irregular.

“There is no escaping the fact that dirty power imposes a far greater burden on network equipment like transformers,” says one electricity expert. There are also concerns about demand spikes from electric vehicle charging putting old transformers, switchgear and cables under heavy strain.

My worry is that an avalanche of equipment failures could put the whole network in a terrible mess. Years of thin orders have killed off firms like Hackbridge and Hewittic which built the gear during the great construction wave in the 1960s and early 1970s. GEC has gone, and companies like ABB have closed their British factories. The UK now has just one transformer plant - GE Vernova - based in Stafford. The average delivery time for a step up transformer is currently running at around 200 weeks in the US.

In a Linked in post, Simon Gallagher accused me of relying on “unnamed sources”, and my article of lacking supporting data and adopting an unduly alarmist tone. I wish it was alarmist. But I am not sure it is shouting “fire” to warn that our regulatory system may have left us worryingly dependent on ageing gear, with insufficient engineers to build or install replacements if needed in a hurry. It hardly looks like a good place.

What we must hope is that our old equipment keeps working while we rebuild the supply chain and train up all the skilled engineers needed. “It’s hard to tell when equipment like this is going to start failing,” says Tim Stone, an infrastructure and energy expert. “ What I fear is that it could resemble Ernest Hemingway’s description of going bankrupt in the way it happens - first slowly then suddenly.”

Interesting article, thank you. Out of interest, did you ask Mr Gallagher for a more comprehensive data set ? Data for only 3 years and “just three of the 12” DNOs seems very thin to arrive at any sensible conclusion.